In the first part of the Twentieth Century there was an artist whose work could be seen everywhere. He graced multiple magazine covers, book illustrations, advertisements. He was the highest paid illustrator of his time. His skills were held in awe by fellow artists and his style was aped by many.

No, it wasn't Norman Rockwell, but Joseph Christian Leyendecker-- known as J.C. Leyendecker.

He was born in 1874 and lived until 1951. If you want more biographical stuff head on over to Wikipedia. This is Maine-ly Painting, not Maine-ly Biographies after all. What I want to show are some of his beautiful paintings.

Last year I took a trip to a Newport, Rhode Island to visit a museum called the National Museum Of American Illustration. They have work from Howard Pyle, N.C. Wyeth, many Maxfield Parrish's, several Rockwells but it was a painting by Leyendecker (and they have many of his) that made my jaw drop. I knew of his work, but seeing his colors, design and mastery of technique in person was an almost religious experience.

Leyendecker did not use photographs. He painted from models only. He made countless preparatory sketches and full-size studies before he tackled the painting. He was not at all above trashing a painting and starting all over if he felt his first (second or third) attempt wasn't up to snuff. That habit drove his art editors nuts, but they lightened up when they saw the finished work. Work like this:

Take a closer look at that horse:

No one else did it like Joe!

No muddy colors on that one! Every brushstroke was loaded with just the right color, chroma and value.

Do yourself a favor and click on these to see how he incorporated his underpainting with the final color application. You can see how he danced and played his local colors on top and around the umber color lay-in, then finished with perfectly tasteful highlights. It looks super easy-- it is not.

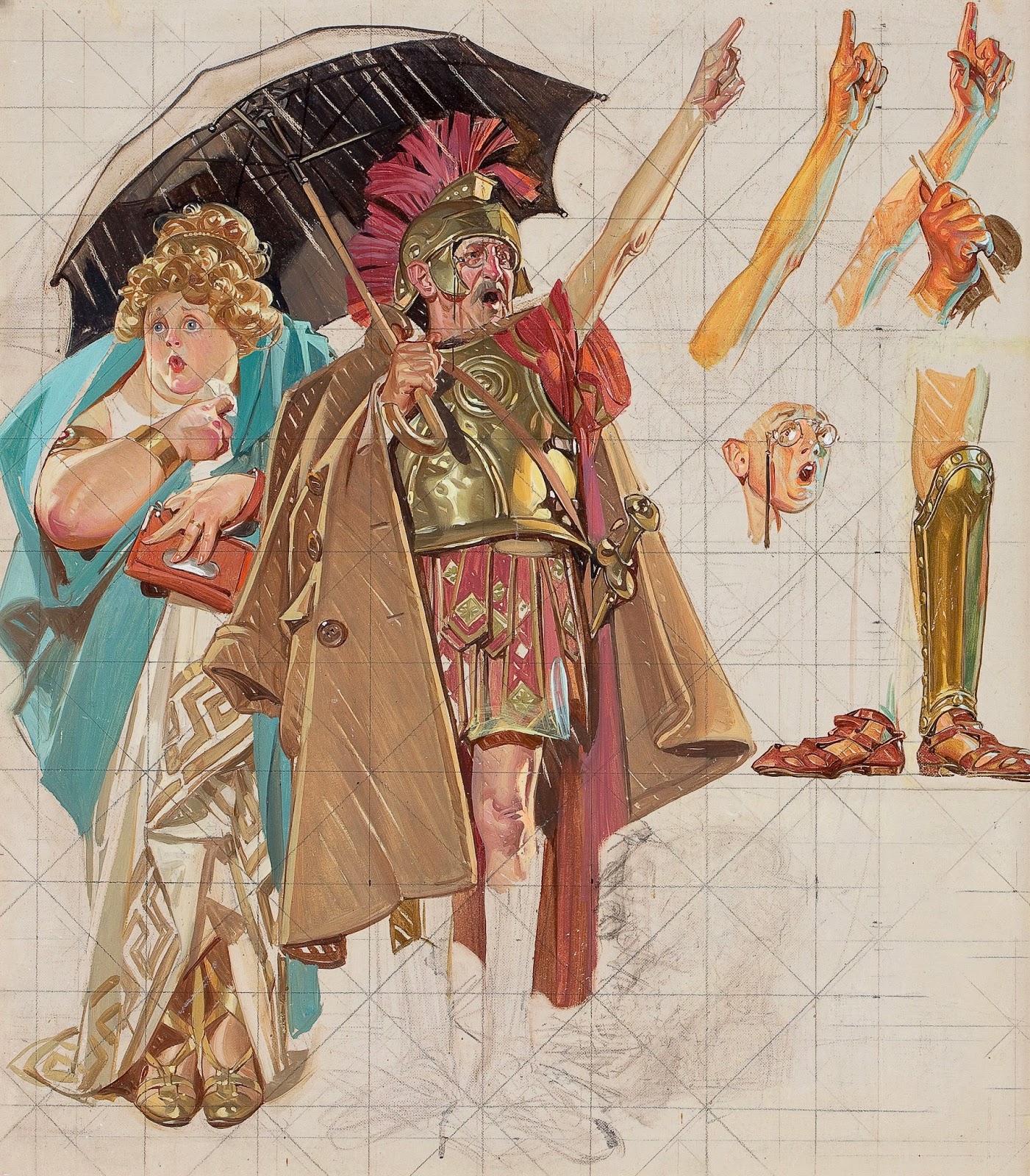

I mentioned his countless studies a moment ago. Here are a couple that show his thought process not only of the painting, but the best way to approach the subject.

I love this one-- The guy inadvertently looking like a Roman Emperor as he hails a cab. Look how Leyendecker noticed he didn't have Caesar's right hand positioned correctly to hold the umbrella, so he painted a correct note there on the right of the canvas. Above that you can see him working out the most effective way to have the guy's finger point to sell the joke. Leyendecker always gridded these oil sketches so he could transfer them accurately onto another canvas.

Here's another stunning sketch showing his decision making:

Hhmmm... what works better? The peeling knife pointed up?, at an angle? What about the thumb position-- would that work better? Should I show the peelings falling into the bowl? It's this amount of prep work that he did that bought him fame and the mansion on the hill that was the envy of the other illustrators.

Along with many others, Norman Rockwell idolized Leyendecker. But unlike most, Rockwell developed a friendship with the great master. In his delightful book My Adventures As An Illustrator, he tells of his years knowing both J.C. and his illustrator brother Frank when they all lived in New Rochelle, New York in the 1930's.

There's more to Leyendecker's fascinating story; How his paintings became synonymous with the Arrow Shirt Man, his homosexuality, his dysfunctional relationships. But I'll leave that for you to find out. Eventually, it was Leyendecker's iconic style that brought about his own down-fall. By the mid 1930's advertisers wanted something fresher and more realistic-- not associated with the Naughts and Roaring Twenties. You know, more Rockwell-like. Leyendecker got fewer and fewer commissions as a result and died penniless, alone and forgotten in 1951. A sad end to a proud and extremely talented man.

Or is it? Recently with the upswing in interest of paintings from the Golden Age of illustration, his work is fast becoming more and more desirable. Studies like the ones I've shown here could have been yours for a couple of hundred bucks just ten years ago. Now they fetch tens of thousands, and his finished paintings done for the Saturday Evening Post go for much more. There is a whole new appreciation for the Artist that once upon a time everyone thought was the greatest of them all.

J.C. Leyendecker

.

%2Bof%2BDown%2BThe%2BMtn%2B24X24.jpg)